.

I read books. I exclusively spend the time on my daily commute reading books, and I on average read between two and three non-fiction books per month (my performance goal is to read 25 pages (or more) per weekday and another 25 pages per weekend, for a minimum of 150 pages per week).

I usually cluster 3-5 books that touch on some specific topic into a "batch", because reading books that relate to a topic and to each other creates a "conversation" between the books I read and it enhances my experience and my learning. The topic of the batch of books I write about below is "collapse" (or the threat/spectre of societal collapse).

I've in fact published more than 55 blog posts about "books I've read". They used to be a regular feature on the blog and the first such post was published in December 2010 and the latest concerned books I read during the first half of 2017 (but the blog post was published one year later, so I had a year-long backlog of writing about books that I had read). Each blog post always refers back to the previous such blog post so it should be possible to track them all down by following a daisy-chain that travels backwards in time.

Let's say I published all of these 55 blog posts between 2011-2017 (a 7-year long period) and that I published no such blog posts between 2018-2024 (again a 7-year long period). Let's further assume that I on average reported on reading four books in each blog post. That would mean that I read ≈ 220 books during a period of 7 years, or around (or possibly slightly more than) 30 books per year. It could also be that I have read upwards to another 200 books since 2018. I could probably track all or most of them down since I carefully note what day I started and what day I finished reading a book inside the book itself. I might do that - but I'm not going to write blog posts about all books that I have read during the last 7 years! I will however write about books that I read from now on, starting with these four books about "collapse":

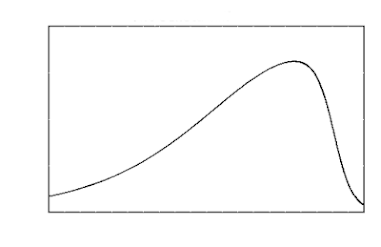

Ugo Bardi's book "Before the Collapse: A guide to the other side of growth" (2020) treats a serious topic but does so with wit, wisdom and humor. The starting point of the book is the "Seneca curve" (or the "Seneca effect" or the "Seneca cliff"), i.e. the idea that growth is slow, but collapse is rapid :

Roman Philosopher Seneca stated that "

It would be some consolation [...] if all things would perish as slowly as they come into being; but as it is, increases are of sluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid". So "collapse" is "

a rapid, uncontrolled, unexpected, and ruinous decline of something that had been going well before" (p.x). Bardi's book is a contribution to the under-researched questions of how things fall apart (a relationship, a company, a nation or a civilisation), i.e. it's a contribution to the non-existent "science of collapse". Over time, most things fall apart and when it's time, one problem leads to another, many things gang up and go bad all at once and collapse ensues. But collapse does not always need to be something that is only bad:

"The basic idea of the Seneca strategy is that the attempts to stave off collapse tend to worsen it. [A] useful skill derived from the Seneca strategy is how collapse can be exploited to get rid of old and useless structures, and organisations. [...] You probably have in mind your government, but it is also possible to think of much smaller systems: plenty of people try to keep their marriage together beyond what's reasonable to do and in many cases divorce, the collapse of a marriage, is the best options. But a company may also become unfit to survive in the market, burdened by obsolete products, outdated strategy, and unmanaged organisation. Bankruptcy is the way we call collapse in this case and, again, it is a way to start again from scratch." (pp.xii-xiii).

The book is full of witty, clever ideas and formulations and it's a treat to read it! Instead of raving about the book, I'll just add a few more quotes from it. If these don't convince you to read the book, then nothing I say will:

"Compulsive gamblers face [a Seneca cliff that] may start from one of the windows of an upper floor of the casino building."

"Typically, models telling people that they have to change their ways are the most likely to be disbelieved or ignored."

"Monetary insolvency is just a quantified version of breaking a promise."

"Fictionalized catastrophes are surely less threatening than those that are described as likely to happen for real. [...] it may be that the only way for our mind to cope with possible catastrophes to come is to see them as fairy tales."

"The reason why depletion [is] neglected in the debate is [...] the human tendency to discount the future, in other worlds to think that an egg today is better than a chicken in the future."

I thought I would like Jim Bendell's "Breaking together: A freedom-loving response to collapse" (2023) since I very much liked his previous (edited) book "Deep Adaptation: Navigating the Realities of Climate Chaos". But I didn't like it very much and it has something to do with the author's voice and his tone throughout the book. As apart of Bardi (above), Bendell takes himself very seriously and it at times feels like he is a zealot and that he believes he is the only person who knows the truth.

That doesn't mean there aren't many things that are interesting in the book and the first half (chapters 1-7) discuss economic collapse, monetary collapse, energy collapse, biosphere collapse, climate collapse, food collapse and societal collapse. I found the chapter about food collapse particularly frightening with it's enumeration of six global trends that work in parallell, that strengthens each other and that spell bad news for humanity (all 8.2 billion of us); 1) we are hitting biophysical limits of food production, 2) we are poisoning or destroying the biosphere that agriculture depends on, 3) current food production relies on declining fossil fuels, 4) climate chaos is constraining food production, 5) food demand is growing rapidly (and can't easily be reduced) and 6) the industrial food system prioritises efficiency and profits over residence and equity.

"Many people who have been working on sustainability topics have their income and self-respect enmeshed in the story that they are helping to change organsiations and societies for the better. The possibility that such efforts have failed is a challenge to their identity. [...] Desire to avoid difficult emotions explains why people don't want to accept that we are in an era of collapse. [...] as middle-class professionals we are statistically far more likely to be apologists for the established societal order than working classes or less educated persons" (pp.264-265).

This quote is also about Bendell himself and about his previous career - about a time when he believed that benevolent companies would save the world by adopting and working towards attaining the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or some other such top-down framework. But the quote is also worrying because it implies that "a little knowledge is a dangerous thing". A lot of knowledge (and a pinch or two of wisdom) is good, but perhaps it's better to know nothing than to know some, but believe you know enough or a lot? This puts a lot of responsibility on me as a university teacher. Am I preaching false hope if I imply that we can fix problems facing humanity? And are my colleagues preaching false hope because they can't handle (their own) difficult emotions of fears for their own and their children's future?

I bought Thomas Homer-Dixon's "Commanding hope: The power we have to renew a world in peril" (2020) because I liked his previous book "The upside of down" (2006) very much. But then I for some reason put it aside and didn't read it for several years.

Homer-Dixon is a very good writer (not all researchers are), and it was a pleasure to read his book as he weaves different stories together, including the story of Stephanie May, who campaigned against nuclear testing at the end of the 1950's and in the 1960's. She worked tirelessly against all odds because she was convinced she was doing the right thing for her country, her children and all children in the world. So the story of Stephanie May, and a central message of Homer-Dixon's book, is how to find / carve out / create a space that is both "feasible" and "enough" and to work towards what you believe is right even when success seems implausible. And we know we can change the world because it has been done before (lex Stephanie May):

"Instead of giving up on hope, or losing it, we need to find it again, reimagine it, and reinvigorate it as a potential source of strength [but] It should be honest, not delusional; passionate, not weak; astute, not naive, and brave, not timid. Most importantly, if we're going to avoid thet downward spiral of resignation and loss of agency, it must be powerful, not passive. It must give us a real sense of purpose for positive action" (p.60).

I in particular thought that Homer-Dixon's thinking about the connection between uncertainty and hope were surprising, counterintuitive and therefore refreshing:

"While uncertainty can quite reasonably provoke fear - fear of the unknown - it can also give us grounds for hope, because it creates a mental space in which we can imagine positive possibilities" (p.75).

If nothing is pre-determined and if there is uncertainty, then there is also hope - even when things look bleak!

David Fleming's book "Surviving the future: Culture, carnival and capital in the aftermath of the market economy" (2016) is a curious choice of book, because I have no idea of why I bought it. I must have read about it and become impressed by it, but I have no recollection of where I read about it nor what impressed me. When I read the foreword, I learned that Fleming died in 2010 and that the book was edited and published posthumously.

Despite the fact that I don't know why I bought it, it was an interesting read. It sings the praise of localism and it's thus not a coincidence that Rob Hopkins, the founder of the

Transition Network, has written the foreword. From the back of the book:

"Surviving the future [...] lays out a powerfully different vision for a new economics in a post-growth world. The subtitle - Culture, carnival and capital in the aftermath of the market economy - hints at Fleming's vision. He believed that the market economy will not survive its inherent flaws beyond the early decades of this century and that its failure will bring great challenges, but he did not dwell on this: "We know what we need to do. We need to build the sequel, to draw on inspiration which has lain dormant, like the seed beneath the snow."

Fleming also assumes that the end (collapse) is not very far away, although he refers to it as "descent", but he doesn't dwell on it because he is already thinking about what comes after. Since Fleming has such an alternative view of the world and of what will become of it, he arrives at and elaborates on many interesting but (again) counterintuitive conclusions of his, which could be disturbing to anyone who is steeped in the current social and economic system and who has problems imagining alternatives:

"The question to consider, therefore, is not whether the crash will happen, but how to develop the skills, the will and the resources necessary to recapture the initiative and build the resilient sequel to our present society. It will be the decentralised, low-impact human ecology which has always taken the human story forward from the closing down of civilisations: small-scale community, closed-loop systems, and a strong culture" (p.8).

.

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar